Library systematizer extraordinaire

by Pip Stromgren

[ Originally published in the Daily Hampshire Gazette on Saturday, June 26, 2004 ]

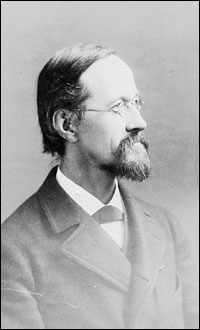

Hanging over the reference librarians’ desk in Northampton’s Forbes Library is a portrait of a late-middle-aged gentleman wearing a black jacket, white shirt and black bow tie. In contrast to the sparse hair on his head, he sports a lush mustache and gray-flecked beard. There is a hint of a smile on his mouth and his eyes behind the wire-rimmed glasses appear observant and kind.

This is Charles Ammi Cutter, the first director of the Forbes. Cutter’s greater claim to fame, however, is his invention of the Expansive Classification scheme on which the current Library of Congress cataloging system is partially based. The portrait, by Massachusetts artist W.H.W. Bicknell, was painted in 1906, three years after Cutter’s death, presumably based on an earlier photograph.

Cutter was born in Boston on March 14, 1837, the second son of Caleb and Hannah Bigelow Cutter. His mother died a month later. His father remarried and when his new wife had a baby, two-year-old Charles Ammi was sent to live with his grandfather and his three maiden aunts in West Cambridge.

The aunts, who were independently wealthy, raised Cutter as their own, including later paying his tuition at Harvard College. One of the aunts was the town librarian so Cutter was exposed to books from an early age. Slight in build, of somewhat frail health and very nearsighted, he much preferred reading to sports. Later on in life, however, he was to enjoy both outdoor activities and dancing.

In 1850, after his grandfather’s death, Cutter and his aunts moved to Cambridge. The following year, at the age of 14, he became a freshman at Harvard. Four years later, he graduated Phi Beta Kappa and third in his class.

In 1856, honoring his late grandfather’s wish, Cutter entered Harvard Divinity School, where he worked in the school’s library compiling a new catalog of its holdings. In 1860, he took the first step in his lifelong career in library science by joining the Harvard College library staff as assistant to Dr. Ezra Abbott, the head cataloguer.

The library was the largest in the country at the time, and for the next eight years, Abbott and Cutter collaborated on a new cataloging system for its collections. Unlike most of the contemporary library catalogs which were in the form of published volumes, Abbott and Cutter used index cards, thus allowing the flexibility of adding or deleting items at will instead of having to wait until the next catalog came out.

In 1868, at age 31, Cutter was appointed librarian of the Boston Athenaeum, where he was to spend the next 25 years. As at Harvard, his first job was to compile a catalog of the library’s collections. Drawing on his past experience, Cutter also wrote Rules for a Dictionary Catalog in 1876. The first of its kind, the book established his reputation in the library world; it became the leading textbook on systematic dictionary cataloging, going through four editions.

During his tenure at the Athenaeum, Cutter introduced several practices still familiar today, including loan cards placed in a pocket glued to the inside of rear book covers, an inter-library loan program, and home deliveries to housebound patrons.

His most ambitious project, the Expansive Classification scheme, was started in 1880. It was designed in seven stages, the first being for very small libraries and the seventh for the largest ones. Cutter’s stated goal was to “prepare a scheme applicable to collections of every size, from the village library in its earliest stages to the national library with a million volumes.”

His system, which became known as the Cutter number or “Cutter,” was an alpha-numeric device for representing words or names by using one or more letters followed by one or more Arabic numerals treated as decimals. But although the Library of Congress still uses Cutter numbers as a partial basis for their cataloging system, it is the Dewey decimal system invented by his contemporary and ultimate rival, Melvil Dewey, that has become the most familiar worldwide, partly due to the fact that Cutter never completed his. The seventh volume, still in working format, was on his desk at the Forbes when he died.

The 1880s and 1890s were difficult years for Cutter professionally. Although he and Dewey had worked together to help establish the American Library Association, they now came into conflict over its direction and leadership.

In addition, the latest group of trustees of the Athenaeum did not approve of some of the changes Cutter was making at the library, in particular the classification system he was trying to implement. The conflict apparently came to a head in 1893 when the trustees tried to unofficially censure him. Convinced that the situation was not likely to improve, Cutter handed in his resignation.

Cutter’s personal life also had its problems. While working at the Harvard Library, he met Sarah Fayerweather Appleton, one of the first female assistants in its cataloging department. They were married on May 21, 1863, and over the next five years, they had three sons. The household, which included two of Cutter’s aunts (one died in 1857) plus one of his wife’s sisters and her husband, was hard to maintain on a librarian’s salary.

To supplement his income, Cutter wrote articles and took on extra work indexing and cataloging scholarly works. The Cutters also suffered major personal losses over the years: their second son, Phillip, died in 1883, and the youngest, Gerald, in 1898.

After leaving the Boston Athenaeum in 1893, Cutter spent some time travelling around Europe, ostensibly to “get away from libraries.” Before his departure, however, he wrote to the trustees of the newly formed Forbes Library in Northampton, offering to buy books, photographs, music and works of art for its budding collection. The trustees accepted his offer and allotted him $50,000 for this purpose. When he returned a year later, Cutter was offered the post of librarian at the Forbes.

In his first annual report, Cutter recalled his first summer at the library in 1894, before it officially opened. With the help of his staff, which consisted of five untrained young women assistants, a few high school and Smith College students, and one janitor, he began the task of unpacking, sorting and shelving the more than 3,000 books he had purchased in Europe. The job proved so daunting that the official opening date, originally set for January 1, 1895, was delayed until July 1.

Cutter’s vision for the Forbes, in his own words, was for “a new type of public library which, speaking broadly, will lend everything to anybody in any desired quantity for any desired time.” There were to be no bothersome rules and children would be welcome.

In another of Cutter’s major departures from the standard practice in most libraries of the time, the Forbes’ patrons were free to browse the open stacks rather than having to request books at the front desk, which a staff member would then fetch.

Over the nine years he spent at the Forbes, Cutter continued to experiment with new ideas and practices, establishing branch libraries, and instituting a traveling library system (the fore-runner of today’s bookmobile service) to serve small towns in western Massachusetts. In 1902, he set up the library’s Art and Music Department, which today includes a priceless collection of local photographs, and created a separate children’s room and programs.

He was very involved with local schools, often bringing art works from the library’s collection to show students. His staff worked closely with the city’s grade school teachers who were allowed to borrow books to use in their classes; a similar service was provided for Smith College students.

In Northampton, Cutter boarded at 109 Elm Street (boarding houses of that era provided a bedroom, shared bathroom, and meals), and possibly also on South Street for a while, both addresses being within easy walking distance of the library.

His wife, who was a Bostonian born and bred, was apparently reluctant to leave her hometown altogether and lived only part of the year in Northampton. City street directories show, however, that shortly before his death, Cutter and his wife moved into 21 Massasoit Street, the former home of Calvin Coolidge.

In the spring of 1903, Cutter suffered an almost fatal bout of pneumonia. He returned to work at the Forbes that summer but suffered a relapse and while recuperating in Walpole, New Hampshire, he died on September 6, 1903, at the age of 66. His nephew, William Parker Cutter, who had previously worked as librarian for the United States Department of Agriculture and also at the Library of Congress, succeeded his uncle as librarian at the Forbes.

Were he alive today, Cutter would no doubt be gratified to know that the Forbes is still using the Cutter Classification system to keep track of its collections.

In addition to Cutter’s portrait in the reference room, his pottery mug with a picture of the Forbes superimposed on one side is in the library’s Hampshire Room for Local History and Special Collections. According to Elise Feeley, the mug was probably given to Cutter when he left Harvard, the image of the library being added at a later date. The original roll top desk that he used is still in the office currently occupied by Janet Moulding, the recently elected ninth director of the library.

© 2004 The Daily Hampshire Gazette; used by permission.